News & information

Economics

In mid-November the Postal Service will announce its full-year Fiscal 2014 financial results. At of the end of August 2014, it had a $1.3 billion operating profit, so the 2014 full-year operating results are on track to be very good.

However, the bottom-line net income will include a $5.7 billion expense for retiree health benefits (RHB) pre-funding, which it has to report in the net income line even when it isn’t paid. The net income line will also include a large workers’ compensation accounting adjustment—an additional negative impact of $1 billion or more this year, due to falling interest rates. Neither of these expenses reflects anything about Postal Service business operations during the year, and so each should be excluded when evaluating annual business results or when comparing year-to-year results.

We’ve said a lot about pre-funding in the past, but you might be curious about the workers’ compensation expense. Two parts comprise this expense: an annual “cash” expense, which reflects the actual cost of workers’ compensation claims during the year, and a workers’ compensation accounting adjustment, which simply reflects changes in the Postal Service’s long-term workers’ compensation liability estimate.

The second part of this expense, the workers’ compensation accounting adjustment, is purely an on-paper accounting adjustment. When the Postal Service increases its long-term workers’ compensation liability estimate on its balance sheet, it has to reflect a related “expense” in its current year income statement. (The income statement is the financial document that the Postal Service refers to when reporting its annual results.) This particular income statement “expense” does not reflect any cash payments or charges that the Postal Service paid during the year. It is simply a mechanical result of the Postal Service’s increasing or decreasing of its long-term workers’ compensation liability estimate on its balance sheet.

Each quarter, the Postal Service plugs new interest rates into its workers’ compensation accounting model to reflect the ups and downs of market interest rates. These plug-ins move the balance sheet liability estimate either up or down. Changes in the balance sheet liability estimate translate into a corresponding income statement expense.

Unlike the relatively steady workers’ compensation cash payments each year (payments for workers’ compensation claims), the long-term workers’ compensation liability is very volatile and goes up or down every quarter based on changes in discount rates (that is, interest rates) during the year. As the Postal Service explained in its 2013 financial statements, “An increase of 1% in the discount rate would decrease the September 30, 2013 liability and 2013 expense by approximately $1.7 billion. A decrease of 1% in the discount rate would increase the September 30, 2013 liability and 2013 expense by approximately $2.1 billion.” So, these discount rate changes can really have an impact on the bottom line, even though they don’t reflect anything about the Postal Service’s business performance or even the changes in the number of people receiving workers’ compensation.

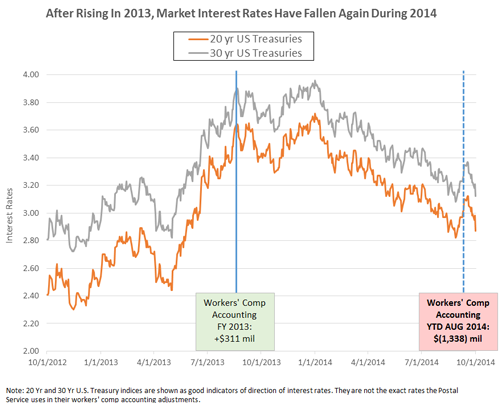

This year so far, the Postal Service has projected that it will have a more than $1.3 billion expense related solely to workers’ compensation accounting adjustments. Last year, conversely, the workers’ compensation accounting adjustment actually added $300 million to the bottom line due to rising interest rates. The cause of this $1.6 billion swing? During FY2013, market interest rates rose. During FY2014, market interest rates fell. To get a better idea of how interest rates changed in FY2013 and FY2014, and how these movements resulted in workers’ compensation accounting adjustments, take a look at the following chart. We do not know exactly which interest rates the Postal Service uses in its model, but U.S. Treasury rates provide a good indication about the overall direction of U.S. interest rates.